Many books and websites note that the famed “hot line” communication link between the Pentagon and the Kremlin was established on August 30, 1963.

Press reports about this new tool, intended to provide a possible way to avoid a nuclear war between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), soon cemented the term hot line into our language.

It also added a new plot device and the image of the red phones into movies and TV shows.

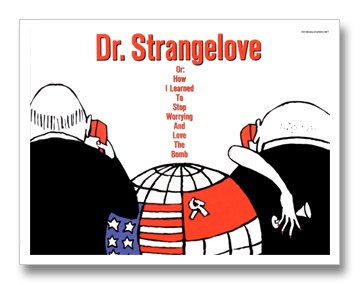

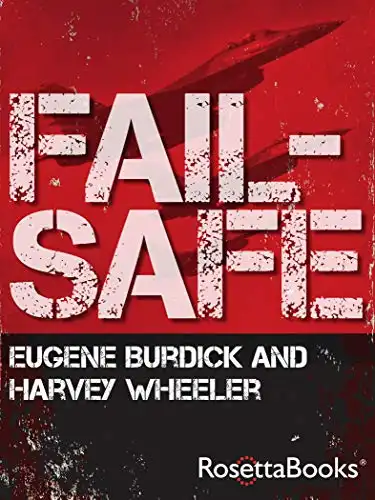

Two of my favorite examples were in movies released not long after the new link was established: Fail-Safe (1964) and Dr. Strangelove, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

.

The term hot line (sometimes given as the single word hotline) had actually been used previously in other contexts, but not in the sense of the international hot line established in 1963.

That use is generally credited to Jess Gorkin (1936-1985).

Gorkin was the respected and influential editor of Parade Magazine, the widely-circulated Sunday newspaper insert.

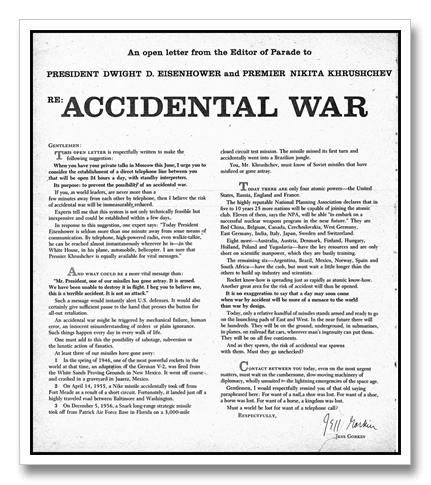

In the March 20, 1960 issue of Parade, Gorkin published an open letter to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Soviet Union’s Premier Nikita Khrushchev, titled “RE: ACCIDENTAL WAR.”

In it, he urged them to consider: “the establishment of a direct telephone line between you…to prevent the possibility of an accidental war.”

He ended his letter with the rhetorical question: “Must a world be lost for want of a telephone call?”

Gorkin didn’t use the term hot line in that open letter, but he did use it in a subsequent series editorials in Parade in 1960, promoting the idea to presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon.

According to language maven William Safire’s great Political Dictionary, Gorkin’s editorial in the October 30, 1960 issue of Parade mentioned an internal “hot line” that the US Strategic Air Command (SAC) maintained for emergency communications.

Gorkin suggested that SAC’s “red telephone” system was a model for the communication link he believed the US and USSR should establish.

After Kennedy was elected President, Gorkin ran more editorials pushing the hot line idea.

And, after the US and USSR came to the brink of nuclear Armageddon in October 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis, Kennedy and Khrushchev decided it was indeed a pretty good idea.

On April 23, 1963, Kennedy sent a personal letter of thanks to Gorkin for promoting the concept, calling it “an excellent example of the most constructive aspects of our free press.”

Gorkin proudly published the letter in Parade.

On June 20, 1963, in Geneva, President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev signed an agreement to create the crisis communication system Gorkin had suggested. The Washington-Kremlin hot line officially went live on August 30, 1963.

However, despite what we’ve seen in movies and TV shows, there never were red phones in the offices of the President of the United States and the Premier of Russia.

The hot line was actually a secure teletype connection between the offices of the Pentagon and the Kremlin. No phones, red or otherwise, were involved.

Sorry, movie fans.

As I was researching this post, I noticed there’s a fairly recent book titled Hotline that gives the term a whole new meaning. It’s a racy novel described with this memorable blurb: “A sex worker and a trust fund brat…It’s like Romeo and Juliet, but with less stabbing and slightly fewer dick jokes.” I haven’t read it, but if you do, let me know how it is.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions? Email me or post them on my Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading and viewing…