On April 19, 1951, General Douglas MacArthur made a high-profile “farewell address” to a joint meeting of both houses of Congress.

Eight days earlier, he’d been fired as the top commander of the American forces in the Korean War by President Harry Truman, essentially for having the gall to publicly criticize Truman’s denial of his request to nuke Red China (in retaliation for sending troops to fight against the U.S. in Korea).

Truman later famously explained: “I fired him because he wouldn’t respect the authority of the President…I didn’t fire him because he was a dumb son of a bitch, although he was.”

Today, with hindsight, most people would likely support Truman’s decision to avoid World War III and affirm the authority of the Commander-in-Chief.

But in 1951, Truman’s firing of MacArthur was highly controversial — and highly politicized by Truman’s Republican adversaries.

MacArthur was one of America’s most renowned generals during World War II.

Among other things, he was known for making and ultimately keeping the legendary vow “I shall return!” — his promise to return to liberate the Philippines from Japanese control after being forced to escape and leave many of his troops there early in 1942.

On September 2, 1945, MacArthur presided over the official surrender of the Japanese, thus ending that war. He then oversaw the American occupation and initial peacetime revitalization of Japan.

In 1950, when the Korean War broke out, President Truman tapped MacArthur as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces who were fighting with South Korea against the North Koreans and their backer, Communist Red China.

MacArthur was well-known and well-liked by most Americans and many believed that the spread of Communism had to be stopped to prevent a “domino effect.”

That didn’t stop the feisty Democratic President from firing him after the general wrote a letter critical of Truman’s decision to avoid further escalation of the war and sent it to Joseph William Martin, Jr., the Republican leader in the House of Representatives.

Martin read the letter aloud on the floor of Congress on April 5th. It was a clear poke in Truman’s eye. Six days later, Truman fired MacArthur.

To poke Truman again, the Republicans invited MacArthur to make a speech to Congress on April 19.

Much of MacArthur’s “farewell address” focused on “the Communist threat.”

He ominously warned that if Communism were allowed to spread in Southeast Asia it would “threaten the freedom of the Philippines and the loss of Japan and might well force our western frontier back to the coast of California, Oregon and Washington.”

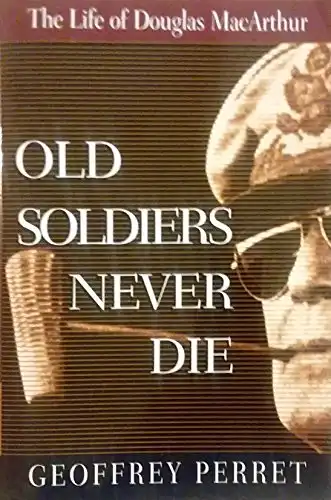

Most of that Cold War rhetoric is now forgotten. The thing that is most remembered from MacArthur’s speech is his famous quote: “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.”

It was part of the closing of his address, in which he said:

“When I joined the Army, even before the turn of the century, it was the fulfillment of all of my boyish hopes and dreams. The world has turned over many times since I took the oath on the plain at West Point, and the hopes and dreams have long since vanished, but I still remember the refrain of one of the most popular barrack ballads of that day which proclaimed most proudly that ‘old soldiers never die, they just fade away.’ And like the old soldier of that ballad, I now close my military career and just fade away, an old soldier who tried to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty. Good-bye.”

As MacArthur noted, the line “old soldiers never die, they just fade away” is not something he coined. It comes from a song that was popular with British soldiers during World War I, called “Old Soldiers Never Die.”

The barracks room song was a parody of the hymn “Kind Words Never Die.” And, unlike the ending of MacArthur’s farewell address, the lyrics of the Army song are more satiric than schmaltzy.

There are several different versions. Here are the lyrics recorded by the late, great quote and phrase maven Eric Partridge in his Dictionary of Catch Phrases :

“Old soldiers never die,

Never die, never die,

Old soldiers never die —

They simply fade away.

Old soldiers never die,

Never die, never die,

Old soldiers never die —

Young ones wish they would.”

Ironically, that and other early versions of the song poked fun at Army life and at career soldiers and officers like MacArthur.

However, after MacArthur cited the song in his farewell speech, Gene Autry rewrote the lyrics to create a more respectful version that specifically praised the general. The last verse of Autry’s rendition says:

“Now somewhere, there stands the man

His duty o’er and won

The world will ne’er forget him

To him we say, ‘Well done.’”

President Truman had a different reaction to MacArthur’s farewell speech.

When asked about it in one of the interviews recorded by Merle Miller for the book Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman (1974), Truman said it was “nothing but a bunch of damn bullshit!”

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on the Famous Quotations Facebook page.

Related reading and viewing…