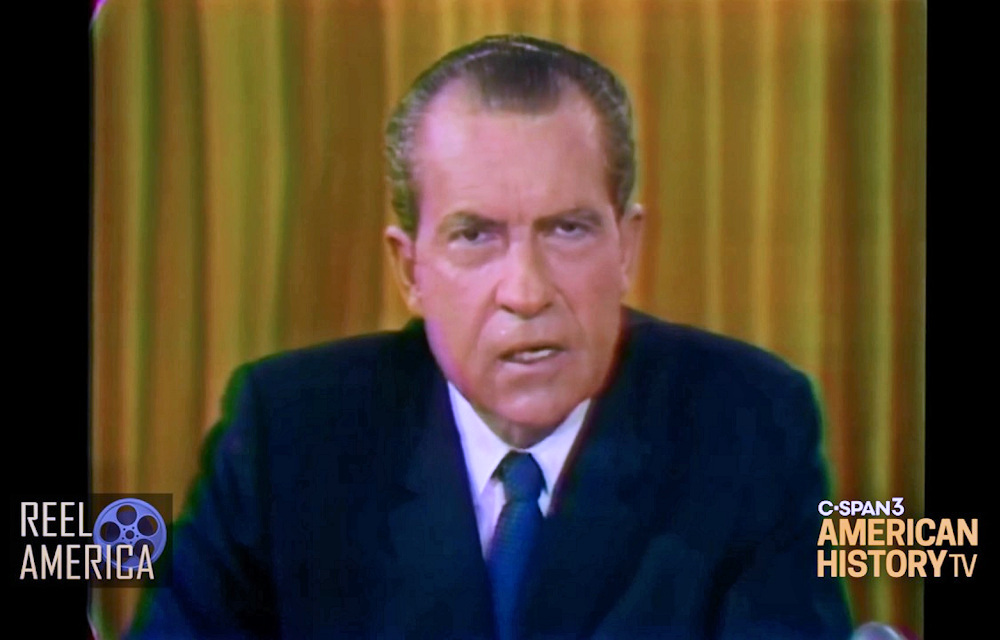

On November 3, 1969, President Richard M. Nixon (1913–1994) made a televised address to the nation about the war in Vietnam that popularized one of the most famous political phrases of the 20th century: “the silent majority.”

In the speech, Nixon appealed to Americans to support his plan to end the war in Vietnam through what he called a gradual “Vietnamization” policy—shifting the fighting to South Vietnamese forces while withdrawing U.S. troops.

The speech was delivered just 19 days after the massive Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam demonstrations on October 15, 1969, when hundreds of thousands of people across the country protested the war.

Near the end of the speech, Nixon said:

“Let historians not record that when America was the most powerful nation in the world we passed on the other side of the road and allowed the last hopes for peace and freedom of millions of people to be suffocated by the forces of totalitarianism. And so tonight—to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans—I ask for your support.”

It was a shrewd political move. Nixon portrayed the demonstrators filling the streets as a noisy minority—and the millions of citizens watching quietly at home as the people who represent the true moral center of the country. He portrayed his Vietnamization plan as a way to achieve ”peace with honor.”

The next day, the New York Times reported that telegrams and letters of support flooded the White House. Nixon’s approval rating soon soared from around 50% to more than 80%.

“His ‘Silent Majority’ address helped him maintain support for continuing the war with the goal of an ultimate withdrawal of American troops—a goal that was not accomplished until 1975, and then ignominiously, not “with honor.”

Although Nixon’s speech made “the silent majority” a famous term, it wasn’t coined by him or his main speechwriter, William Safire (who later became a columnist and author who wrote about the history of political phrases).

In the 19th century, dead people were sometimes referred to as “the silent majority” in literature and obituaries. For example, The Times (London), August 10, 1868 obituary for the then famous British general Colin Campbell, 1st Baron Clyde (1792 – 1863) said: “Lord Clyde, after a long and honourable service, has gone to join the silent majority.”

Uses of the phrase in a political context also date back to the 1800s. It became a metaphor for people who have a certain political view but may express it less publicly than people who have the opposite view.

For example, when Warren G. Harding was campaigning for president in 1920, he contrasted people he described as “the silent, thoughtful majority” with socialists, anarchists, and pro-union labor militants whose protests and other activities were grabbing headlines after World War I.

Although some politicians have claimed to have a “silent majority” of supporters when the facts suggested otherwise, Harding’s faith proved correct. He won the 1920 election in a landslide against his Democratic opponent James M. Cox, who supported a liberal agenda, including labor protections, child welfare laws, and women’s suffrage.

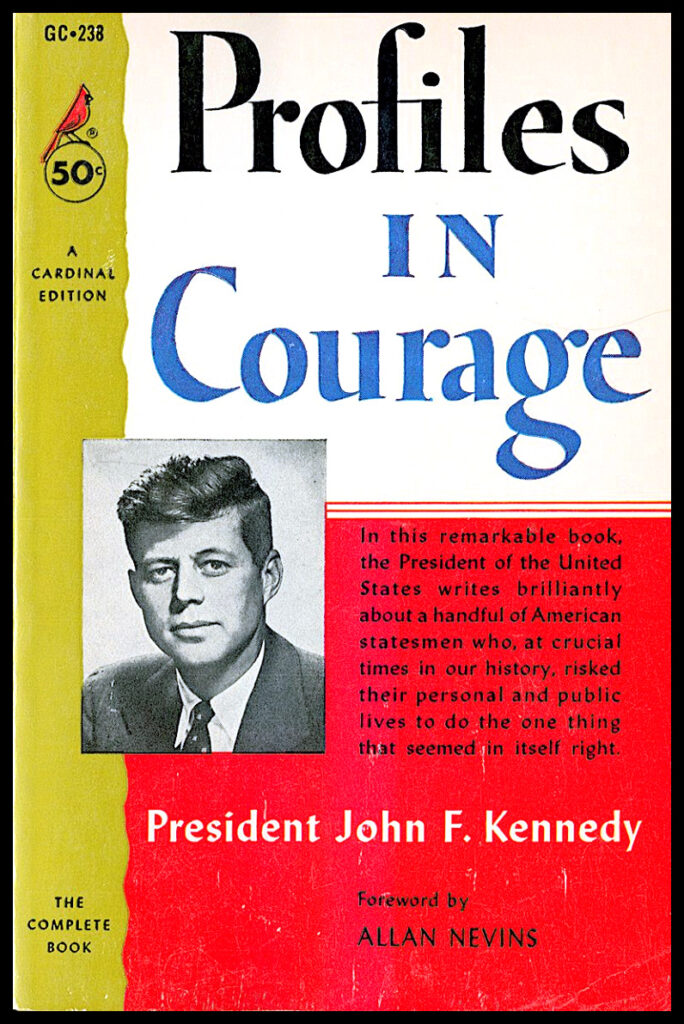

Ironically, in 1956, John F. Kennedy, Nixon’s 1960 presidential rival, used the phrase in his Pulitzer Prize–winning book Profiles in Courage. Describing legislators who bravely defied public clamor, Kennedy wrote that “some of them may have been representing the actual sentiments of the silent majority of their constituents in opposition to the screams of a vocal minority.”

Nixon’s Vice President, Spiro T. Agnew, also used it before Nixon’s November 3, 1969 address. In a speech on May 9, 1969, Agnew declared: “It is time for America’s silent majority to stand up for its rights.”

The phrase took on new life in the 1970s and 1980s when Ronald Reagan invoked often it to describe ordinary Americans who felt overlooked by the political and media elite.

For example, in his August 3, 1980 campaign speech in Chicago, he said: “The silent majority of Americans is tired of being told by the voices of a noisy minority that this country has passed its zenith.”

In 1979, Evangelical leader Jerry Falwell echoed the term by calling his conservative movement the “Moral Majority.” That led to a popular bumper poster that mocked the movement’s self-righteous tone that said: “The Moral Majority is neither.”

In 1991, while running for president, Bill Clinton created a version of the phrase he used in stump speeches, claiming he was an advocate for “the forgotten middle class.”

Over the decades there have also been many reuses, variations and parodies of “the silent majority” in pop culture. .

As a lifelong science fiction fan, my own favorite pop culture use is in the “Decision 3012” episode of the animated sci-fi comedy Futurama (Season 9, Ep. 3, first aired in 2012).

It includes a joke about politics that references Soylent Green, the famous 1973 dystopian movie. In that film, the Earth is so overpopulated and polluted that the government feeds poor people a food product called “Soylent Green,” which is secretly made from the corpses of other poor people.

That Futurama episode features a recurring character who is Richard Nixon’s head, preserved and alive in a jar using some weird technology. Nixon’s head is portrayed as a power-hungry politician who cares little about common people but pretends he does.

During a campaign speech, he tries to use his famed 1969 phrase but accidentally starts to say “the soylent majority.” “In this time of crisis,” he intones, “I call upon the soylent majo— I mean, silent majority.”

The slip suggests he’s even worse than Nixon was in the ‘60s, when he earned the nickname “Tricky Dicky.” In Futurama he’s become the kind of slimy politician in Soylent Green who’d be willing to secretly harvest the bodies of poor people to make food for other poor people.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Questions Questions? Post them on the Famous Quotations Facebook page or email me at the email address shown on the “About” page for this blog.